You can survive: Truly alone in the wilderness: Lost in Yellowstone for 37 days pretty much without equipment, food, clothing or shelter. ‘After wandering away from the rest of the expedition on September 9, 1870, Everts managed to lose the pack horse which was carrying most of his supplies. He ate a songbird and minnows raw, and a local thistle plant to stay alive; the plant (Cirsium foliosum or elk thistle) was later renamed “Evert’s Thistle” after him. Everts’ party searched for him for a while, and his friends in Helena offered a reward of $600 to find him. “Yellowstone Jack” Baronett and George A. Pritchett found Everts, suffering from frostbite, burn wounds from thermal vents and his campfire, and other wounds suffered during his ordeal, so malnourished he weighed only 50 pounds (23 kg). One stayed with him to nurse him back to health while the other walked 75 miles (121 km) for help; in spite of their assistance, Everts denied the men the payment of the reward, claiming he could have made it out of the mountains on his own.’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truman_C._Everts

Available here: https://archive.org/stream/thirtysevendayso30924gut/pg30924.txt Free downloads: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/30924.mobile

SCRIBNER’S MONTHLY

VOL. III. November, 1871. No. 1 THIRTY-SEVEN DAYS OF PERIL

[Illustration: Imaginary Companions.]

I have read with great satisfaction the excellent descriptive articles

on the wonders of the Upper Yellowstone, in the May and June

numbers of your magazine. Having myself been one of the party

who participated in many of the pleasures, and suffered all the perils

of that expedition, I can not only bear testimony to the fidelity of

the narrative, but probably add some facts of experience which will

not detract from the general interest it has excited.

A desire to visit the remarkable region, of which, during several

years’ residence in Montana, I had often heard the most marvelous

accounts, led me to unite in the expedition of August last. The

general character of the stupendous scenery of the Rocky Mountains

prepared my mind for giving credit to all the strange stories told of

the Yellowstone, and I felt quite as certain of the existence of the

physical phenomena of that country, on the morning that our company

started from Helena, as when I afterwards beheld it. I engaged in the

enterprise with enthusiasm, feeling that all the hardships and

exposures of a month’s horseback travel through an unexplored region

would be more than compensated by the grandeur and novelty of the

natural objects with which it was crowded. Of course, the idea of

being lost in it, without any of the ordinary means of subsistence,

and the wandering for days and weeks, in a famishing condition, alone,

in an unfrequented wilderness, formed no part of my contemplation. I

had dwelt too long amid the mountains not to know that such a thought,

had it occurred, would have been instantly rejected as improbable;

nevertheless, “man proposes and God disposes,” a truism which found a

new and ample illustration in my wanderings through the Upper

Yellowstone region.

On the day that I found myself separated from the company, and for

several days previous, our course had been impeded by the dense growth

of the pine forest, and occasional large tracts of fallen timber,

frequently rendering our progress almost impossible. Whenever we came

to one of these immense windfalls, each man engaged in the pursuit of

a passage through it, and it was while thus employed, and with the

idea that I had found one, that I strayed out of sight and hearing of

my comrades. We had a toilsome day. It was quite late in the

afternoon. As separations like this had frequently occurred, it gave

me no alarm, and I rode on, fully confident of soon rejoining the

company, or of finding their camp. I came up with the pack-horse,

which Mr. Langford afterwards recovered, and tried to drive him along,

but failing to do so, and my eyesight being defective, I spurred

forward, intending to return with assistance from the party. This

incident tended to accelerate my speed. I rode on in the direction

which I supposed had been taken, until darkness overtook me in the

dense forest. This was disagreeable enough, but caused me no alarm. I

had no doubt of being with the party at breakfast the next morning. I

selected a spot for comfortable repose, picketed my horse, built a

fire, and went to sleep.

The next morning I rose at early dawn, saddled and mounted my horse,

and took my course in the supposed direction of the camp. Our ride of

the previous day had been up a peninsula jutting into the lake, for

the shore of which I started, with the expectation of finding my

friends camped on the beach. The forest was quite dark, and the trees

so thick, that it was only by a slow process I could get through them

at all. In searching for the trail I became somewhat confused. The

falling foliage of the pines had obliterated every trace of travel. I

was obliged frequently to dismount, and examine the ground for the

faintest indications. Coming to an opening, from which I could see

several vistas, I dismounted for the purpose of selecting one leading

in the direction I had chosen, and leaving my horse unhitched, as had

always been my custom, walked a few rods into the forest. While

surveying the ground my horse took fright, and I turned around in time

to see him disappearing at full speed among the trees. That was the

last I ever saw of him. It was yet quite dark. My blankets, gun,

pistols, fishing tackle, matches–everything, except the clothing on

my person, a couple of knives, and a small opera-glass were attached

to the saddle.

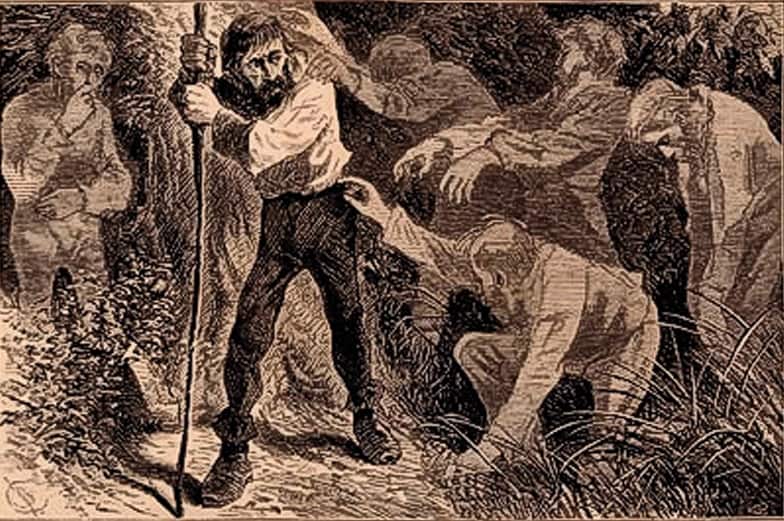

[Illustration: “The Last I Ever Saw of Him.”]

I did not realize the possibility of a permanent separation from the

company. Instead of following up the pursuit of their camp, I engaged

in an effort to recover my horse. Half a day’s search convinced me of

its impracticability. I wrote and posted in an open space several

notices, which, if my friends should chance to see, would inform them

of my condition and the route I had taken, and then struck out into

the forest in the supposed direction of their camp. As the day wore on

without any discovery, alarm took the place of anxiety at the prospect

of another night alone in the wilderness, and this time without food

or fire. But even this dismal foreboding was cheered by the hope that

should soon rejoin my companions, who would laugh at my adventure, and

incorporate it as a thrilling episode into the journal of our trip.

The bright side of a misfortune, as I found by experience, even under

the worst possible circumstances, always presents some features of

encouragement. When I began to realize that my condition was one of

actual peril, I banished from my mind all fear of an unfavorable

result. Seating myself on a log, I recalled every foot of the way I

had traveled since the separation from my friends, and the most

probable opinion I could form of their whereabouts was, that they had,

by a course but little different from mine, passed by the spot where I

had posted the notices, learned of my disaster, and were waiting for

me the rejoin them there, or searching for me in that vicinity. A

night must be spent amid the prostrate trunks before my return could

be accomplished. At no time during my period of exile did I experience

so much mental suffering from the cravings of hunger as when,

exhausted with this long clay of fruitless search, I resigned myself

to a couch of pine foliage in the pitchy darkness of a thicket of

small trees. Naturally timid in the night, I fully realized the

exposure of my condition. I peered upward through the darkness, but

all was blackness and gloom. The wind sighed mournfully through the

pines. The forest seemed alive with the screeching of night birds, the

angry barking of coyotes, and the prolonged, dismal howl of the gray

wolf. These sounds, familiar by their constant occurrence throughout

the journey, were now full of terror, and drove slumber from my

eyelids. Above all this, however, was the hope that I should be

restored to my comrades the next day.

Early the next morning I rose unrefreshed, and pursued my weary way

over the prostrate trunks. It was noon when I reached the spot where

my notices were posted. No one had been there. My disappointment was

almost overwhelming. For the first time, I realized that I was lost.

Then came a crushing sense of destitution. No food, no fire; no means

to procure either; alone in an unexplored wilderness, one hundred and

fifty miles from the nearest human abode, surrounded by wild beasts,

and famishing with hunger. It was no time for despondency. A moment

afterwards I felt how calamity can elevate the mind, in the formation

of the resolution “not to perish in that wilderness.”

The hope of finding the party still controlled my plans. I thought, by

traversing the peninsula centrally, I would be enabled to strike the

shore of the lake in advance of their camp, and near the point of

departure for the Madison. Acting upon this impression, I rose from a

sleepless couch, and pursued my way through the timber-entangled

forest. A feeling of weakness took the place of hunger. Conscious of

the need of food, I felt no cravings. Occasionally, while scrambling

over logs and through thickets, a sense of faintness and exhaustion

would come over me, but I would suppress it with the audible

expression, “This won’t do; I must find my company.” Despondency would

sometimes strive with resolution for the mastery of my thoughts. I

would think of home–of my daughter–and of the possible chance of

starvation, or death in some more terrible form; but as often as these

gloomy forebodings came, I would strive to banish them with

reflections better adapted to my immediate necessities. I recollect at

this time discussing the question, whether there was not implanted by

Providence in every man a principle of self-preservation equal to any

emergency which did not destroy his reason. I decided this question

affirmatively a thousand times afterwards in my wanderings, and I

record this experience here, that any person who reads it, should he

ever find himself in like circumstances, may not despair. There is

life in the thought. It will revive hope, allay hunger, renew energy,

encourage perseverance, and, as I have proved in my own case, bring a

man out of difficulty, when nothing else can avail.

It was mid-day when I emerged from the forest into an open space at

the foot of the peninsula. A broad lake of beautiful curvature, with

magnificent surroundings, lay before me, glittering in the sunbeams.

It was full twelve miles in circumference. A wide belt of sand formed

the margin which I was approaching, directly opposite to which, rising

seemingly from the very depths of the water, towered the loftiest peak

of a range of mountains apparently interminable. The ascending vapor

from innumerable hot springs, and the sparkling jet of a single

geyser, added the feature of novelty to one of the grandest landscapes

I ever beheld. Nor was the life of the scene less noticeable than its

other attractions. Large flocks of swans and other water-fowl were

sporting on the quiet surface of the lake; otters in great numbers

performed the most amusing aquatic evolutions; mink and beaver swam

around unscared, in the most grotesque confusion. Deer, elk, and

mountain sheep stared at me, manifesting more surprise than fear at

my presence among them. The adjacent forest was vocal with the songs

of birds, chief of which were the chattering notes of a species of

mockingbird, whose imitative efforts afforded abundant merriment. Seen

under favorable circumstances, this assemblage of grandeur, beauty,

and novelty would have been transporting; but, jaded with travel,

famishing with hunger, and distressed with anxiety, I was in no humor

for ecstacy. My tastes were subdued and chastened by the perils which

environed me. I longed for food, friends and protection. Associated

with my thoughts, however, was the wish that some of my friends of

peculiar tastes could enjoy this display of secluded magnificence,

now, probably, for the first time beheld by mortal eyes.

The lake was at least one thousand feet lower than the highest point

of the peninsula, and several hundred feet below the level of

Yellowstone Lake. I recognized the mountain which overshadowed it as

the landmark which a few days before, had received from Gen. Washburn

the name of Mount Everts; and as it is associated with some of the

most agreeable and terrible incidents of my exile, I feel that I have

more than a mere discoverer’s right to the perpetuity of that

christening. The lake is fed by innumerable small streams from the

mountains, and the countless hot springs surrounding it. A large river

flows from it, through a canon a thousand feet in height, in a

southeasterly direction, to a distant range of mountains, which I

conjectured to be Snake River; and with the belief that I had

discovered the source of the great southern tributary of the Columbia,

I gave it the name of Bessie Lake, after the

“Sole daughter of my house and heart.”

During the first two days, the fear of meeting with Indians gave me

considerable anxiety, but, when conscious of being lost, there was

nothing I so much desired as to fall in with a lodge of Bannacks or

Crows. Having nothing to tempt their cupidity, they would do me no

personal harm, and, with the promise of reward, would probably

minister to my wants and aid my deliverance. Imagine my delight, while

gazing upon the animated expanse of water, at seeing sail out from a

distant point a large canoe containing a single oarsman. It was

rapidly approaching the shore where I was seated. With hurried steps I

paced the beach to meet it, all my energies stimulated by the

assurance it gave of food, safety and restoration to friends. As I

drew near to it it turned towards the shore, and oh! bitter

disappointment, the object which my eager fancy had transformed into

an angel of relief stalked from the water, an enormous pelican,

flapped its dragon-wings, as if in mockery of my sorrow, and flew to a

solitary point farther up the lake. This little incident quite

unmanned me. The transition from joy to grief brought with it a

terrible consciousness of the horrors of my condition. But night was

fast approaching, and darkness would come with it. While looking for a

spot where I might repose in safety, my attention was attracted to a

small green plant of so lively a hue as to form a striking contrast

with deep pine foliage. For closer examination I pulled it up by the

root, which was long and tapering, not unlike a radish. It was a

thistle. I tasted it; it was palatable and nutritious. My appetite

craved it, and the first meal in four days was made on thistle-roots.

Eureka! I had found food. No optical illusion deceived me this time; I

could subsist until I rejoined my companions. Glorious counterpoise to

the wretchedness of the preceding half-hour!

Overjoyed at this discovery, with hunger allayed, I stretched myself

under a tree, upon the foliage which had partially filled a space

between contiguous trunks, and fell asleep. How long I slept I know

not; but suddenly I was roused by a loud, shrill scream, like that of

a human being in distress, poured, seemingly, into the very portals of

my ear. There was no mistaking that fearful voice. I had been deceived

by and answered it a dozen times while threading the forest, with the

belief that it was a friendly signal. It was the screech of a mountain

lion, so alarmingly near as to cause every nerve to thrill with

terror. To yell in return, seize with convulsive grasp the limbs of

the friendly tree, and swing myself into it, was the work of a moment.

Scrambling hurriedly from limb to limb, I was soon as near the top as

safety would permit. The savage beast was snuffing and growling below

apparently on the very spot I had just abandoned. I answered every

growl with a responsive scream. Terrified at the delay and pawing of

the beast, I increased my voice to its utmost volume, broke branches

from the limbs, and, in the impotency of fright, madly hurled them at

the spot whence the continued howlings proceeded.

Failing to alarm the animal, which now began to make a circuit of the

tree, as if to select a spot for springing into it, I shook, with a

strength increased by terror, the slender trunk until every limb

rustled with the motion. All in vain. The terrible creature pursued

his walk around the tree, lashing the ground with his tail, and

prolonging his howlings a